Egypt’s latest wave of privatisation, spearheaded by the Sovereign Fund of Egypt (TSFE), has sparked heated debate. While the government touts it as a bold step towards economic liberalisation, critics question whether the process is truly transparent, whether the state is getting fair value, and whether ordinary Egyptians stand to benefit—or lose—from the sell-off.

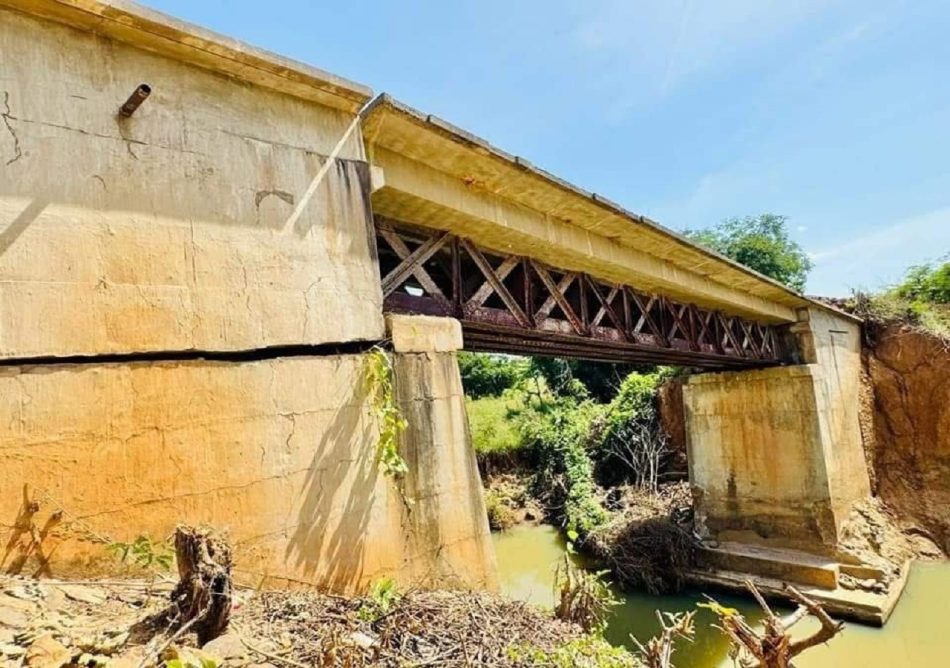

With stakes in five major state-owned firms—including National Petroleum Services Co., Silo Foods, and Wataneya Company for Roads—set to hit the market by 2026, the government insists this will attract foreign investment and reduce public debt. But is this optimism justified, or is Egypt repeating past mistakes of undervaluing and mismanaging public assets?

Egypt’s economy has been in turmoil since the 2011 revolution, exacerbated by currency devaluation, inflation, and a heavy reliance on IMF bailouts. The current privatisation drive, backed by an $8 billion IMF loan, aims to slash public debt, boost private sector growth, and stabilise the economy.

Yet, history casts a long shadow. Egypt’s previous privatisation efforts in the 1990s and 2000s were marred by allegations of corruption, asset stripping, and job losses. A 2011 report by Egypt’s Central Auditing Agency found that many state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were sold at below-market prices, with well-connected businessmen reaping the benefits while workers suffered.

Fast forward to today—has anything changed? The government claims the process is transparent, with top-tier advisory firms like PwC, EFG Hermes, and Boston Consulting Group overseeing the sales. However, critics argue that military-linked enterprises dominate the list of assets up for grabs, raising concerns about preferential treatment.

“When state assets are sold to entities with close ties to the government or military, it raises red flags,” says Dr. Amr Adly, an economist at the Carnegie Middle East Center. “The lack of competitive bidding and independent valuation means we don’t know if Egypt is getting a fair deal.”

A 2024 report by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) found that several recent privatisation deals lacked public disclosure of sale terms, leaving room for undervaluation. For instance, when Banque du Caire was partially privatised in 2023, analysts argued its valuation failed to account for prime real estate holdings.

Privatisation often promises efficiency, but at what cost? In the case of Eastern Company S.A.E (Egypt’s tobacco monopoly), the 2023 partial sale led to layoffs and price hikes, squeezing consumers already battling inflation. Similar fears loom over Silo Foods and National Petroleum Services—will new owners prioritise profits over public welfare?

“Efficiency gains shouldn’t come at the expense of workers or consumers,” argues labour rights activist Hossam El-Hamalawy. “If privatisation just means higher prices and fewer jobs, then who is this really benefiting?”

The IMF has praised Egypt’s privatisation drive, calling it “critical” for reducing state dominance. Yet, critics argue the Fund’s rigid conditions—fuel subsidy cuts, austerity measures, and rapid asset sales—may force Egypt into fire sales, undermining long-term economic sovereignty.

“The IMF’s prescription assumes privatisation automatically leads to better management, but that’s not guaranteed,” says development economist Dr. Rabab El-Mahdi. “If buyers are more interested in asset-stripping than reinvestment, Egypt could end up worse off.”

Other African nations offer cautionary tales. Nigeria’s 2000s privatisation of power assets saw little improvement in electricity supply, while South Africa’s mismanaged SOEs remain a drag on growth. Conversely, Morocco’s gradual, regulated approach to selling state assets has yielded mixed but more stable results.

For Egypt to avoid past pitfalls, experts recommend:

Public disclosure of sale terms to build trust.

Independent valuations to prevent undervaluation.

Strict post-sale oversight to ensure new owners meet investment and employment targets.

Egypt’s privatisation drive is a gamble. If executed fairly, it could attract investment and ease fiscal pressures. But if history repeats itself, it may deepen inequality, enrich a select few, and leave ordinary Egyptians bearing the cost.

As the TSFE prepares to offload more state assets, one question lingers: Is Egypt selling its future—or saving it?