It’s been dubbed a “turning point” for Mali’s transport infrastructure — the rehabilitation of the Kassaro Bridge in the Kita region, a strategic lifeline for the Bamako-Kayes railway corridor. On Tuesday, April 15, 2025, the Malian Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure inked a 1.6 billion FCFA deal with Chinese construction firm Covec Mali to restore the collapsed bridge within four months. The event was attended by top government officials, including Finance Minister Alousseni Sanou and Transport Minister Dembélé Madina Sissoko, with promises that “the train will whistle again.”

But behind the ribbon-cutting, handshakes, and hopeful headlines lies a more complicated narrative — one of delayed maintenance, foreign dependency, political pressure, and recurring infrastructure failure.

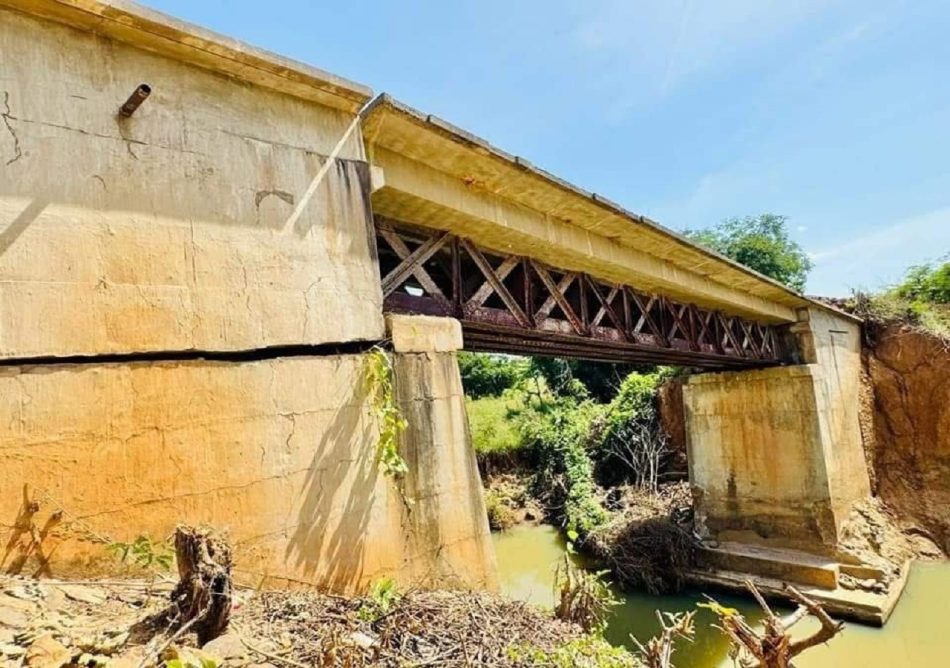

On August 30, 2024, torrential rains swept through southern Mali, leading to the catastrophic failure of the Kassaro Bridge. Over 100 meters of railway embankment were washed away, and the structure’s abutments on both the Kassaro and Sébékoro sides were severely compromised. The collapse wasn’t just physical. It derailed the country’s renewed hopes for rail connectivity, halting traffic that had only resumed in mid-2023 after a five-year suspension.

This interruption also derailed the momentum generated by the 2023 relaunch of the Bamako-Kayes rail line, which itself came at a steep cost — over 6 billion FCFA in government-led investments to restore tracks, stations, and rolling stock. The Kassaro collapse exposed what critics had feared all along: Mali’s railway infrastructure remains fragile and under-resourced, vulnerable not only to climate events but to chronic under-investment and policy neglect.

Enter Covec Mali, a subsidiary of China’s massive China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC), a familiar name across Africa’s infrastructure map. The signed memorandum of understanding pledges that the bridge will be rebuilt in four months, a timeline both ambitious and politically loaded. Covec’s regional director, Zhang Lunkun, offered reassurances of rapid mobilization and quality engineering.

This Chinese intervention is part of a broader, well-documented pattern: Beijing’s growing footprint across Africa’s transportation, energy, and digital sectors. Mali is no exception. For some observers, this partnership is a necessary alignment with an experienced international contractor. For others, it reflects a worrisome over-reliance on foreign hands to solve domestic problems — especially when those problems stem from years of ignored maintenance and poor infrastructure governance.

The involvement of the World Bank as a “strategic partner” was also highlighted by Minister Sissoko, pointing to a multi-stakeholder approach to Mali’s rail revival. Still, this patchwork of international support raises a critical question, “Why is Mali perpetually dependent on outside actors to manage its core infrastructure lifelines?”

The bridge’s failure was not just an engineering disaster; it quickly became a political headache. President of Transition, Army General Assimi Goïta, declared a state of emergency following the 2024 floods and pledged 4 billion FCFA from the national budget for flood resilience and emergency repairs. Part of this funding will now support the Kassaro rehabilitation.

This promise is not without symbolism. It represents the state’s attempt to reassert control and responsiveness in a politically fragile environment, where infrastructure is both a tool of legitimacy and a barometer of governance. With elections and political transitions looming, the government needs visible wins — and a functional railway is one such deliverable.

Transport Minister Sissoko’s public assurance that “all conditions are now met” to relaunch rail services is a high-stakes commitment. The question remains, “What happens if deadlines slip or technical issues emerge again?”

Will the public accept another delay? Or will trust in the state’s logistical and governance capacity further erode?

The Malian railway once symbolized national unity and regional trade integration. A reliable train line from Kayes to Bamako could facilitate cargo movement, reduce transport costs, and boost inter-regional commerce, especially for landlocked Mali, heavily reliant on road networks that are increasingly vulnerable to climate shocks and insurgent threats in the Sahel.

However, despite efforts to breathe new life into rail, the industry remains un-derserved, under-capitalized, and dangerously over-politicized. The 2023 resumption was largely ceremonial, and passenger services have been erratic. As of early 2024, freight services remained sporadic and inefficient, hampered by outdated locomotives, insecure stations, and a lack of operational autonomy.

The Kassaro bridge project might fix a critical node, but systemic challenges persist — from institutional fragmentation to corruption in procurement, and the absence of a comprehensive national rail strategy. Critics argue that until structural reforms are enacted — not just emergency repairs — Mali’s rail system will remain in a state of managed decline.

China’s role in African infrastructure development is undeniable. From Angola’s highways to Ethiopia’s electric rail lines, Beijing has built more in 15 years than many traditional partners. But the trade-offs are real. Debt exposure, labor concerns, limited local skills transfer, and the potential geopolitical leverage it gives China in the region.

In Mali’s case, Covec’s return is both a solution and a signal — that the state still lacks internal capacity to sustainably manage large-scale public works. This project, while necessary, must not distract from the long-term need to build domestic engineering expertise, institutional resilience, and financial autonomy.

The Kassaro bridge rehab is more than just concrete and steel. It is a litmus test for Mali’s post-conflict reconstruction agenda, a symbol of its aspirations for connectivity and sovereignty, and a cautionary tale about the fragility of progress in the absence of long-term vision.

As work begins and promises pile up, one question resonates across the nation. “Will this bridge truly reconnect Mali — or simply delay the next collapse?”

Only time — and political will — will tell.