In a move loaded with economic and political significance, Gabon has announced the $300 million (approx. 181 billion CFA francs or €275 million) acquisition of Tullow Oil’s assets through its national oil company, Gabon Oil Company (GOC). This landmark deal, unveiled on March 24, 2025, is more than a commercial handshake—it is a bold reclamation of national sovereignty in one of Africa’s oldest oil-producing nations. The acquisition signals a broader pivot from decades of private monopolization and murky influence, most notably by the Beninese oil tycoon Samuel Dossou-Aworet, whose grip on Gabon’s hydrocarbon sector is now dramatically weakened.

For Gabon, this moment is symbolic. It is the first time in recent memory that a major energy asset has returned to the hands of the state, and with it, the hopes of realigning the country’s vast natural wealth with public interest. According to transitional President Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema, the deal is expected to boost the nation’s production capacity from 12,000 barrels per day to a striking 82,000—an almost sevenfold increase. The implications for the country’s economy and governance are immense.

Samuel Dossou-Aworet, once a towering figure in Gabon’s oil corridors, symbolized a broader pattern of foreign economic dominance. As a former advisor to late President Omar Bongo and the mastermind behind the Petrolin Group, Dossou-Aworet built an empire around Gabon’s energy assets. For decades, he operated at the intersection of state power and private capital, often accused of capturing public resources under the guise of technical expertise.

The sale of Tullow Oil’s Gabonese assets—shortly following his acquisition of Shell assets in Nigeria—hints at a strategic retreat from Gabon. Sources within the Ministry of Oil suggest this reflects not just shifting business priorities but also a growing pressure from Libreville to dismantle entrenched external interests.

“This is a strong signal,” one senior official noted anonymously. “Gabon is reclaiming its resources and gradually freeing itself from certain networks of influence.”

Oil is the backbone of Gabon’s economy, accounting for nearly 60% of its exports and more than 30% of its GDP. However, the oil sector has historically operated as a dual economy—highly lucrative but largely disconnected from the everyday lives of most Gabonese. Elite capture, secrecy in licensing contracts, and poor reinvestment of oil profits have long stymied inclusive growth.

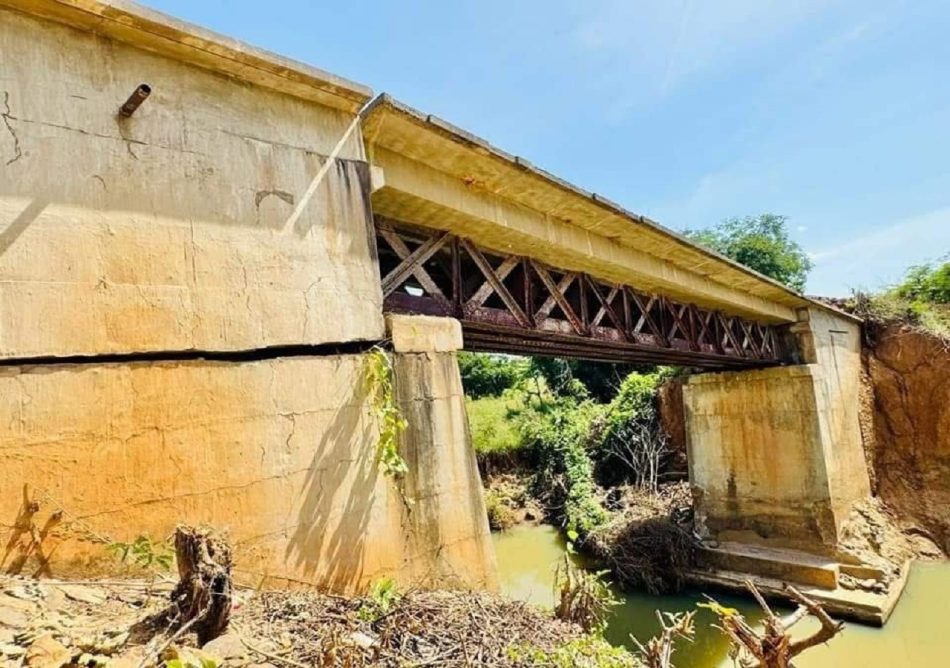

Now, Gabon is aiming for a new trajectory. With GOC in control, the government has an opportunity to reintegrate oil profits into national development, diversify its economy, and strengthen its tourism ambitions. The irony is that while Gabon boasts some of Africa’s most pristine eco-tourism offerings—from Loango National Park to its lush equatorial rainforests—these treasures have often been overshadowed by oil-centric policymaking and weak infrastructure development.

A realignment of oil revenue management could breathe new life into these sectors. “If the government channels even a fraction of these new earnings into sustainable tourism infrastructure, Gabon could emerge as a green luxury destination for high-net-worth travelers,” says Amadou Diallo, a regional tourism analyst. “But it will require discipline, transparency, and vision.”

The acquisition, though historic, is only the beginning. Economists and analysts caution that Gabon’s oil sector remains structurally fragile. The key challenge now is not ownership, but governance. How GOC manages the newly acquired assets—both operationally and financially—will determine whether this transition leads to broad-based development or simply replaces one elite with another.

François Ella, an independent Gabonese economist, captures this sentiment well: “Buying back is one thing. Managing and making these assets profitable in the interest of the Gabonese people is another.”

Indeed, Gabon must still contend with global market volatility, the pressure of the energy transition, and the technical demands of oilfield management. Furthermore, without institutional safeguards, the same patronage networks that characterized the previous era could simply morph under the banner of nationalization.

The state’s pivot to oil nationalism also raises strategic questions about foreign partnerships. With Chinese and Malaysian players increasingly active in Central Africa’s energy markets, Gabon must balance sovereignty with cooperation. Can Libreville forge mutually beneficial deals that retain national control without alienating critical technology and capital providers?

Gabon’s move is not isolated. Across the continent, there’s a quiet but growing trend of resource nationalism. From Nigeria’s push to reform its oil laws to Tanzania’s renegotiation of mining contracts, African states are increasingly demanding greater value from their natural assets.

For Gabon, the Tullow Oil acquisition represents not just a transfer of assets but the possibility of systemic reform—provided the political will is matched with technocratic competence. This moment could redefine how a resource-rich but historically underdeveloped country uses its wealth to serve its people.

As Gabon turns the page on the Dossou-Aworet era, the challenge is clear: make this reclamation more than symbolic. Turn barrels into books, royalties into roads, and crude into a catalyst for inclusive, sustainable growth.

The wells may now belong to the people. Whether the profits follow remains to be seen.